By Hannah Packman, NFU Communications Director

In the last 12 months, food prices at grocery stores have risen 5.6 percent – the largest annual increase in nearly a decade. The severity of price increases vary drastically depending on the product; beef prices, for instance are 25 percent higher than they were a year ago, while those for fruits and vegetables are just 2.3 percent higher.

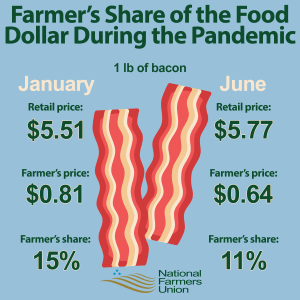

But the extra money consumers are shelling out for their pantry staples isn’t being passed on to the farmers and ranchers who grew that food. In fact, the prices that farmers are currently receiving are, on average, 4.8 percent lowerthan they were last year. Like consumers’ prices, fluctuations in farmers’ prices differ significantly by product: livestock prices are 17 percent below where they were last May, whereas fruit and tree nut prices are 49 percent higher.

Though many variables influence the cost of food, the pandemic is largely responsible for dramatic swings in both consumer and producer prices. Prior to the pandemic, consumers spent roughly equal amounts of money on food at home and food away from home. But pandemic-related business closures and stay at home orders meant that the majority of food expenditures abruptly shifted almost entirely to the former category. The resulting surge in demand at grocery stores likely contributed to the price inflation we’ve seen over the last several months.

These changes have affected farmers’ prices as well – though mostly in the opposite direction. The market for foods primarily prepared and eaten in schools, restaurants, cruise ships, theme parks, and other commercial settings – think lobster, milk and cheese, and potatoes – evaporated overnight. Many farmers, ranchers, and fishermen had nowhere to sell their products, forcing some to bury surplus crops or dump milk. Even those who were lucky enough to find a market often sold at a loss because the sudden drop in demand dragged down prices.

For other farmers and ranchers, there’s been plenty of demand, but supply chain disruptions have prevented them from getting their food to consumers. Nowhere has this been more pronounced than in the meat and poultry industry. At least 370 meatpacking plants, or about 1/3 of the national total, have experienced COVID-19 outbreaks among employees. Dozens temporarily closed or slowed production to prevent further spread of the virus, which cut into processing capacity significantly. At the peak, beef and pork facilities were operating 25 percent and 40 percent below average, respectively. With production backed up, farmers were stranded with animals that couldn’t be processed as well as depressed prices. (It should be noted that there have also been allegations of price fixing among meatpackers, which may have exacerbated price declines.)

Like what you’ve read? Join the conversation at National Farmers Union’s Facebook page.